Email Info@vancetwins.com

Children and Parents Wander the Alleys – Translated Version

ORIGINAL SOURCE: San Francisco · Kim In-jeong (Nonfiction Writer) 2025.09.29

International adoption in Korea has been criticized as virtually state-sanctioned human trafficking.

The existence of Janine, Jenette, and Kyung-sook is proof of this. Those questioning the Korean government have yet to receive a proper answer. The “Mother’s Arms Cemetery” in Paju, Gyeonggi Province, opened in June 2025. The memorial wall within the premises features approximately 700 name tags of international adoptees.

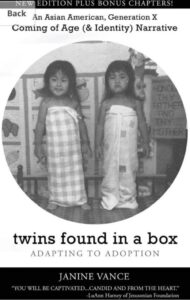

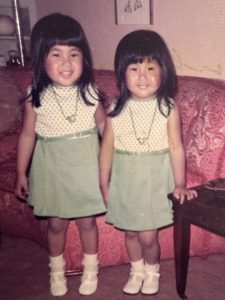

The sisters lived in a 4,000-square-foot house in the woods outside Seattle, USA. They had devout Presbyterian parents and two older brothers. It was a life given to twin sisters adopted from Korea without question. They didn’t even know which of them was the older sister.

Their adoption papers simply stated that they had been found on the street corner in Seoul.

They were taught not to ask more than that. They believed that adopted orphans were saved. The sisters grew up as typical American girls, enjoying McDonald’s hamburgers, Michael Jackson, and roller skating.

Of course, they kept a few secrets.

Clothes with unmarked tags, magazines unopened, boxes piled to the ceiling, and heavy furniture clogged the hallways, leaving the house cramped. Only the older brothers had their own bedrooms, while the twins were given only nooks and crannies.

Their adoptive mother kept a vigilant eye on them, fearing they might touch her belongings or sneak food.

Inviting friends over, like other children their age, was out of the question. After their adoptive father fell 100 feet from a hang-gliding accident and became confined to a wheelchair due to brain damage, their adoptive mother’s compulsive hoarding and depression worsened.

At school, I wanted to be different. I wanted to be a cheerleader — someone who could dance and cheer in front of others. Maybe being a twin would even work to my advantage. But from the very first day of school, I heard racial slurs mocking Asians. The cheerleaders laughed openly at us, saying, “Did you come from China?”

Janine, who was always the more sensitive one, often stood in front of the mirror when she got home. She saw a face that didn’t look like her family’s or her school friends’. As she examined her reflection closely, she secretly began to dislike the features that made her different from white people.

Around the same time Janine was hating her reflection, another Korean-born girl stood before a mirror in a small room of a seaside house in Tønsberg, Norway.

The face staring back at her seemed to say she would never truly belong among “them.” No matter how hard she looked, she could never figure out where her nose, cheeks, or straight black hair came from. It felt like trying to piece together a small fragment of a huge puzzle without any clues. Kyung-sook tormented herself, wondering if she was somehow a mistake — a person who shouldn’t exist.

Her family had fair skin, light blond hair, and big blue eyes.

So did the people she passed on the streets or saw at school. She was always told she was ugly. No one ever explained why she looked different. When she asked her adoptive mother, she was told, “You don’t look any different from the other kids, so stop asking stupid questions and don’t be annoying.”

Children who disappeared “without their parents knowing”

Kyung-sook had been adopted to replace a baby who had died. Since she was little, she’d heard over and over that her parents had to take out a mortgage just to adopt her. Maybe that’s why the beatings never stopped. She was called horrible names — told she was dumber than a monkey. She was often left hungry.

Her adoptive father touched her body.

Her small room wasn’t a place of rest, but a hiding place. She hid in corners and cracks, wishing she could just become part of the wall — or die. Her adoptive parents were soaked in alcohol and cigarettes, and they didn’t even wash her clothes. At school, her different appearance and smell made her the target of relentless bullying. On her way to and from school, instead of friends, she was met with insults and violence. When other kids yanked off her scarf and hat and threw them into the mud, there was no friendship to be found — only isolation.

She was always alone.

The only place she could rest was by the sea. There, hidden from her family and schoolmates, she caught tiny crabs on the beach by herself. She lingered there, not wanting to go home. Each time, she imagined freshly baked bread waiting for her — but deep down, she knew she’d return to hunger.

She hated the face in the mirror.

In 2004, when the Vance twins were 32 years old, they came to Korea for the first time. They were excited — it was their first time meeting other adoptees and seeing so many Koreans — at an event commemorating 50 years of international adoption.

Walking through a dark alley from the cyber cafe, on the way back to the hotel, a strange Korean man suddenly appeared and slowly approached Janine. Janine instinctively recoiled.

From inside his coat, he pulled out an envelope.

https://www.amazon.com/Search-Mother-Missing-International-Adoption/dp/1548423963/r